Jacques Lecoq

By Savithaa Markandu

Jacques Lecoq was never meant to be a theatre pedagog.

His first love was gymnastics. Of course he trained in other sports like swimming and track, but gymnastics was where he discovered the physical poetry of a body in motion. Imagine the clockworks turning in a young Jacques Lecoq’s mind as he swings on the bars. Believe it or not, at these moments Lecoq was observing the geometry and symmetry of a body moving through space; that to compose sharp movements, they had to be highly codified. Amazed? Well it doesn’t stop here.

Lecoq was an intelligent man. During the Second World War he persisted his study in physical education and sports, specializing in sports therapy as well as rehabilitation work for young people and disabled people. After the war, there was an unfortunate need to discipline children to be stronger so that they could defend their country. Many sports practitioners developed physical training methods for movement and efficient body use, focusing on “the ability of laboring bodies to fulfill prescribed tasks” (Evans, 2012). Lecoq however, was inquisitive about what it meant to be in a body and how far one could stretch its possibilities.

“He saw how a man with paralysis could organize his body in such a way that he could re-learn to walk ”

Jacques Lecoq training students in sports

Lecoq’s interactions with patients taught him that the body remembers; that there was significance in knowing one’s body and how to use it. His work in rehabilitation and physiotherapy made him realise the potential of the body and steered his interest towards movement and physicality.

JAcques Lecoq’s first revelation of theatre was when he met Jean-Marie Conty at Bagatelle College for physical education.

By then, Conty was an international basketball player, a pilot for the Aéropostal Company with Saint-Exupery, and he was in charge of physical education for all of France. To top it off, he was Jacques Lecoq’s passport to the discovery of mime. Conty was friends with Antonin Artaud as well as Jean-Louis Barrault, who was a director and actor who revived post-war French theatre. Both artists exposed Conty to theatre and mime, instilling in him a curiosity about the bond between sports and physical expression. It was thanks to Conty that Lecoq discovered the physicality of Barrault’s mime movement and became attracted to theatre. His first theatre training took place with Travail et Culture (TEC), where he applied his unique athletic knowledge to movement choreography. This was where the bridge between sports, theatre and movement began to solidify.

Following the Liberation of France from Nazi invasion (1944), Lecoq and other TEC students linked with Luigi Ciccione, Lecoq’s physical education teacher from college, to form a troupe called Les Compagnons de la Saint-Jean. Together, they celebrated France’s freedom by executing large festive events where they sang, danced and mimed to re-enact historic war stories and victories to public crowds. This was when Jean Dasté approached the troupe to join his company, Les Comédiens de Grenoble, where Lecoq later became a physical trainer. And voila, this was Lecoq’s professional debut in theatre!

“ It was not a question of training athletes, but of training dramatic characters such as a king, a queen-a natural extension of the gestures acquired through sports”

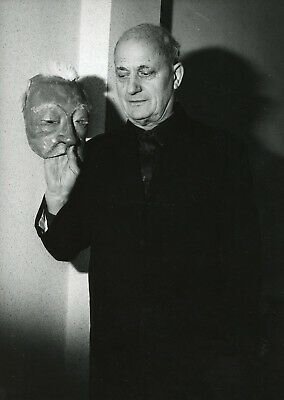

Throughout his profession Jacques Lecoq continued to tie sports to theatre by recognizing that the dramatic gestures were exaggerated forms of athletic movement. Through Dasté, he also discovered masked performance, and Japanese Noh theatre. Drawing inspiration from his teacher, Jacques Copeau, Dasté believed that the mask drove the actor to heavily rely on simple yet magnified gestures to form bodily expressions. This was also reflected in Noh Theatre, which encompassed slow movement and poetic dialogue to physically convey nature and animals in traditional stories. Lecoq was intrigued by masked performance, which intensified his passion for body movement analysis, and the masks became of great use in his teachings later on.

Jean Dasté

In 1948, Jacques Lecoq travelled to Italy to teach at the University of Padua.

Here, he met a sculptor named Amleto Sartori, with whom he built a strong friendship that lasted for decades. Through Sartori, Lecoq was introduced to commedia dell’arte, a humorous theatrical presentation of stereotypical characters performed by acting troupes that travelled around Italy. Sartori and Lecoq used to visit markets and eat at bars out of town, and during their daily encounters with the local community, Lecoq found that commedia dell’arte was also rooted in Italy’s everyday life. Interestingly, Sartori, who offered to sculpt masks for Lecoq, revived the original techniques for making the leather masks of the commedia. Together, they researched the possibility of crafting a new mask, which later on became the neutral mask in Lecoq’s work.

At this point, I can imagine Lecoq walking through a corridor of achievements, and turning around towards the end to say, “But wait, there’s more!”

And more there was. Soon after his buzzing adventure, Lecoq completed major productions with big names like Luciano Berio and Anna Magnani, but his biggest project was yet to come.

“

Through teaching I have discovered that the body knows things about which the mind is ignorant

(Jacques Lecoq 2000)

In 1956, Jacques Lecoq returned to Paris with a reservoir of knowledge, practice and skills accumulated from his Italian sojourn. Having done so much already, what more could he do? Lecoq realized that his experience cooked up a melting pot of politics, history and culture, that could be applied to the body in training. Aspiring to share his journey with others, he devoted himself to teaching and opened the École Internationale de Théâtre Jacques Lecoq.

Lecoq became a significant model in his students’ lives, inspiring them to experiment, make mistakes and learn from the process of theatre making.

“I am nobody […] I am only there to place obstacles in your path, so you can better find your way around them ”

Rather than teaching with a signature style, he aimed to provide his students with sustainable tools that pushed them to make independent discoveries. To find out more about this, stay tuned for another article on Lecoq’s pedagogy and the students whose lives he impacted.

By Savithaa Markandu